2 Chemical Reactions: Stoichiometry and Rates

Chemical reactions are critical to life and critical to the production of food, fuels, materials, chemicals, and pharmaceuticals. Bioprocess Engineers utilize this intersection to produce these valuable and necessary commodities in a cheaper, less resource and energy intensive, lower risk, and more sustainable way. This is done by harnessing the lifeforms that perform valuable chemical reactions and engineering systems to scale up the production of these valuable chemicals for commercial use.

Before we can delve into engineering chemical reactions we must first develop the ability to quantify chemical reactions.

2.1 Stoichometry

The stoichiometry of a chemical reaction tells us what chemical species are consumed and formed in a reaction and in what proportions. Stoichiometry is the basis of our ability to quantify a chemical reaction

Consider the chemical reaction: \[ \ce{Cl2 + C3H6 + 2NaOH -> C3H6O + 2NaCl + H2O} \] It is important to check that this reaction equation is balanced, and therefore satisfies the law of conservation of matter. We will check that this equation is balanced as a review.

Remembering your general chemistry, in order to write a balanced chemical equation the chemical elements (\(j\)) must be conserved, i.e. for each chemical compound/species \(i\) \[\sum_{i} \nu_i N_{ij} = 0\] where \(\nu_i\) is the stoichiometric coefficient for each chemical species containing the element and \(N_{ij}\) is the number of molecules of the element \(j\) in species \(i\).

Within this equation there is a critical convention: The coefficients of the products of a reaction are positive, and the coefficients of the reactants are negative.

So for the reaction above we can make a table for each chemical species and element:

| \(\nu_i N_{ij}\) | \(\ce{Cl2}\) | \(\ce{C3H6}\) | \(\ce{NaOH}\) | \(\ce{C3H6O}\) | \(\ce{NaCl}\) | \(\ce{H2O}\) | \(\sum_{i}\) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| \(\ce{Cl}\) | -1 * 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2*1 | 0 | 0 |

| \(\ce{C}\) | 0 | -1*3 | 0 | 1*3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| \(\ce{H}\) | 0 | -1*6 | -2*1 | 1*6 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| \(\ce{Na}\) | 0 | 0 | -2*1 | 0 | 2*1 | 0 | 0 |

| \(\ce{O}\) | 0 | 0 | -2*1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

You may have used this stoichiometric notation in thermodynamics to calculate the standard Gibbs free energy or standard enthalpy change of a reaction.

This balanced stoichiometric equation tells us then that for every mole of \(\ce{Cl2}\) consumed, one mole of \(\ce{C3H6O}\) will be formed, as long as there is sufficient \(\ce{C3H6}\) and \(\ce{NaOH}\). But how can we figure out if there are sufficient quantities of the other reactants? How can we figure out which reactant is limiting?

2.2 Quantifying the Progress of a Reaction

2.2.1 Extent of Reaction

The extent of reaction is a measure of how far a reaction has progressed at any point in time. To define the extent of reaction we will use the example of a simple batch reactor, imagine a beaker containing fixed amounts of chemicals which are reacting. To define how far the reaction has progressed we start by defining the change in each chemical species throughout the reaction.

At the start of the reaction there are \(n_{i0}\) moles of each \(i\) species in our reaction. At time \(t\) the number of moles of species \(i\) is defined as \(n_i\). We can then define the change in species \(i\) as \(\Delta n_i = n_i - n_{i0}\).

The extent of reaction is a property of the whole reaction not each individual species. So to convert the change in moles of any species, to the extent to which the reaction has progressed, we divide the change in moles of species \(i\) by its stoichiometric coefficient, i.e. \[\xi = \Delta n_i/\nu_i\]

2.2.1.1 ???Questions???

Is the extent of reaction for reactants positive or negative? Is the extent of reaction for products positive or negative?

The extent of reaction is always positive. Be careful about always sticking to the \(\text{final} - \text{initial}\) convention and check the signs of your stoichiometric coefficients.

The extent of reaction can also be defined for continuous (steady state open) systems \[\xi = \Delta \dot n_i/\nu_i\]

2.2.1.2 Limiting Reactant

Extent of reaction is how we calculate the limiting reactant. The limiting reactant is the reactant that is completely consumed in the reaction and prevents the reaction from progressing any further. Therefore the limiting reactant, \(l\), defines the maximum extent of the reaction, because it is completely consumed in the reaction, i.e. \[\xi_{max} = -n_{l0}/\nu_l\]

We can find the limiting reactant by calculating the extent of reaction for each reactant species if it were completely consumed. The limiting reactant has the lowest extent of reaction, i.e. it runs out first if the reaction goes to completion. In reversible reactions, equilibrium will be reached prior to completion and \(\xi\) will always be less than \(\xi_{max}\).

2.2.2 Fractional Conversion

The fraction of the limiting reactant that has been consumed is also frequently used to quantify the progress of a single reaction. Fractional conversion is defined as: \[x_l = \frac{n_{l0} - n_l}{n_{l0}} = 1 - \frac{n_l}{n_l0} \label{eq:frac-conv}\] Fractional conversion can also sometimes be specified for certain species in the reaction, e.g. \(x_A\). This sometimes done when only one species in the reaction can be measured. For a constant volume/density system conversion can also be defined in terms of concentration. \[\frac{C_{A0} - C_{A}}{C_{A0}} = x_A = 1-C_A/C_{A0}\] \[\therefore C_A/C_{A0} = 1-x_A\]

2.2.3 Multiple Reactions, Yield, and Selectivity

If there are multiple reactions happening we can assign each one an extent of reaction and use these to define generation and consumption terms in our material balances. Let’s walk through an example to demonstrate this.

Thiophene (\(\ce{C4H4S}\)) is a problematic contaminant of both biofuels and petroleum because it contains sulfur. A pilot plant for removal of thiophene by hydrodesulfurization has been run with the following results:

| Species | moles fed | moles effluent |

|---|---|---|

| \(\ce{C4H4S}\) | 75.3 | 5.3 |

| \(\ce{H2}\) | 410.9 | 145.9 |

| \(\ce{C4H10}\) | 20.1 | 75.1 |

| \(\ce{H2S}\) | 25.7 | 95.7 |

The following reactions are proposed to occur: \[\ce{C4H4S + 3H2 ->[1] C4H8 + H2S} \\ \ce{C4H8 + H2 ->[2] C4H10}\]

Are the data above consistent with these proposed reactions i.e. do the reactive material balances work out?

To answer this we need to write the material balances on each species. We can assume no accumulation in the reactor in this case, so our General Balance simplifies to \[OUT = IN + GEN - CONS\] Now we can make a table and fill in each species. Let’s skip the symbolic notation here for simplicity \[ \begin{array}{cccccccc} \text{General:} &\text{OUT}& = & \text{IN} & + & \text{GEN} & - & \text{CONS} \\ \ce{C4H4S}: & 5.3 &=& 75.3 &&&-& \xi_1 \\ \ce{H2}:& 145.9 &=& 410.9 &&&-& 3\xi_1 - \xi_2 \\ \ce{C4H10}:& \\ \ce{H2S}: \\ \ce{C4H8}: \end{array} \] OUT and IN values come directly from the table. GEN and CONS values are written in terms of the extents of reactions. It is particularly difficult to write out the balances in terms of conversions for multiple reactions, this is why we introduce extents of reaction. Fill in the last 3 rows of the table for practice.

Now that we have written all of our balances, we can solve for unknowns, the extents of our two reactions. We can do that from the first two species balances above. \[\xi_1 = 75.3 - 5.3 = 70\] \[\xi_2 = 410.19 - 3(70) - 145.9 = 55\] Now to answer the question we need to see if the remaining balances are consistent with these values. If we plug in these values to the other balances are they mathematically correct? If so then the law of conservation of mass is satisfied based on our data and the proposed reactions.

2.2.3.1 ???Questions???

How much butene (\(\ce{C4H8}\)) is in the effluent of the reactor?

Butene is formed in the first reaction and consumed in the second, so \(N_{Be} = 1 \cdot 70 + (-1) \cdot 55 = 15\) mol.

2.2.3.2 Yield Coefficients

A yield coefficient is a fraction consisting of the amount of product formed over the amount of reactant consumed. Thus yield coefficients are kind of like stoichiometric ratios, but they can be written for multiple reactions. They can even be used to describe the “stoichiometry” of enormous numbers of reactions like all of the reactions required for a cell to consume a sugar and produce more cell mass. Yield coefficients (sometimes just called yields) allow us to do simple calculations of the amounts of products formed from some substrate/reactant, or how much reactant is required to form some amount of product.

What is the yield coefficient of butane (\(\ce{C4H10}\)) on hydrogen?

We would specify this as \[Y_{\ce{C4H10}/\ce{H2}} = \frac{\Delta n_{\ce{C4H10}}}{-\Delta n_{\ce{H2}}}\] Yield coefficients are always expressed as positive values.

It is always best practice to carry the species names along with the units when using yields or stoichiometric ratios in calculations. The units of the above yield would be \[\frac{\text{mol } \ce{C4H10}}{\text{mol } \ce{H2}}\]

2.2.3.3 Selectivity

Another way to quantify the progress of multiple reactions, with a particular focus on the desired product, is called selectivity. Selectivity is just a specific yield, the yield of desired product on undesired product, so \[S_{\ce{C4H10}/\ce{C4H8}} = Y_{\ce{C4H10}/\ce{C4H8}} = \frac{\Delta n_{\ce{C4H10}}}{-\Delta n_{\ce{C4H8}}}\]

The generation of undesired products is pretty prevalent in in traditional organic chemistry where different isomers are inevitably formed in most reactions. In biological systems, enzymatic reactions are often stereo-specific mostly alleviating the need for selectivity. However, it is certainly still useful as a metric for optimizing systems, particularly in metabolic engineering.

2.3 Reaction Rates: Quantifying the Dynamics of a Reaction

Reaction rates are simply the rate of consumption of reactants or generation of products.

2.3.1 Species-dependent Reaction Rate

To be useful in designing reactors the reaction rate must be an intensive variable—independent of the size of the reactor. The reaction rate is typically defined in terms of one of the reactants or products of the reaction. The reaction rate is defined as: \[r_i \equiv \text{rate of formation of product }i \left[\frac{\text{ (moles }i \text{ formed)}}{\text{(unit time)(unit reactor)}}\right]\] or \[-r_i \equiv \text{rate of disappearance of reactant }i \left[\frac{\text{ (moles }i \text{ consumed)}}{\text{(unit time)(unit reactor)}}\right]\]

Reaction rates by convention are always positive. We indicate the reaction rate with respect to a reactant by multiplying by \(-1\). This allows us to use the stoichiometry of the reaction to convert reaction rates between species in a reaction, for a stoichiometrically-simple reaction, e.g.

\[ r_1/\nu_1 = r_2/\nu_2 = r_3/\nu_3 = ... = r_i/\nu_i\]

If multiple reactions are taking place the rate of each reaction must be known to calculate the total rate of formation/disappearance of a species: \[r_i = \sum_{k=1}^{R}r_{ki}\] where \(R\) is the number of independent reactions taking place and \(k\) is the specific reaction.

So for example, the following 2 reactions are happening in a batch reactor: \[\ce{A ->[1] 2B} \\ \ce{B ->[2] C}\] The rate of formation of B, then would be the sum of the rate of formation of B from each reaction, but B is a reactant in reaction 2, so this is a negative rate (rate of consumption). \(r_B = r_{1B} - r_{2B}\)

2.3.2 Species-independent Reaction Rates

We can make the reaction rate independent of the species for which it was calculated, and referenced to the reaction itself, by dividing the species-dependent rate by the stoichiometric coefficient for that species in the reaction. \[r \equiv r_i/\nu_i\]

This form of the reaction rate has the advantage of preventing confusion about the rate for one reactant being different from another, but does require that the chemical equation that the rate describes be defined. For example the value of \(r\) would be different for the following two equations \[\ce{N_2 + 3H_2 <=> 2NH_3}\] \[\ce{1/2N_2 + 3/2H_2 <=> NH_3}\]

However, \(r_{N_2}\) would be the same for the two reactions, and \(3r_{N_2} = r_{H_2}\). Fortunately, this species-independent form of the rate equation is rarely used for biochemical reactions. We present it here mostly as a reminder to always check the stoichiometry of the reaction and the units of the rate for consistency, particularly when using data from the literature. This is especially important as for biochemical reactions the symbol \(v\) for velocity of reaction instead of \(r\) for rate. Velocity is frequently defined in terms of the primary product of the reaction, but always check to make sure, subscripts are rarely used to specify how velocity is defined.

2.3.3 Rate Equations

Now that we have defined reaction rates, how do we quantify them? We might suspect, or know from basic chemistry that a reaction is dependent on temperature and the concentration of all of the species participating in the reaction. \[r_A \approx f(T, C_i)\] Based on more than a century of studying chemical kinetics we can lay out some generalizations about chemical reactions to help us understand the general form and properties of reaction rate functions.

2.3.3.1 For single reactions that are essentially irreversible, the effects of temperature and concentration are seperable

This can be described mathematically as: \[-r_A = k(T)f(C_i)\] Here, \(k\), the rate constant is a function of temperature \(T\). Most reactions we will deal with as bioprocess engineers are not simple single irreversible reactions, however this generalization is useful in deriving more complicated reaction mechanisms and often provides a useful starting point when designing reactors.

2.3.3.2 The rate constant \(k\) follows the Arrhenius equation

The Arrhenius equation dictates how typical chemical reaction rates depend on temperature. It has the form \[k(T) = Ae^{-E/RT}\] where \(R\) is the gas constant, \(T\) is the absolute temperature, \(E\) is the activation energy, and \(A\) is the pre-exponential factor or frequency factor of the reaction. The Arrhenius equation dictates that the rate of a reaction increases exponentially with temperature. On the molecular level temperature reflects the kinetic energy of the molecules within the reactor. The more kinetic energy the molecules in a reactor have, i.e. the higher the temperature, the more likely they are to collide, or fluctuate, in the correct orientation to undergo the reaction.

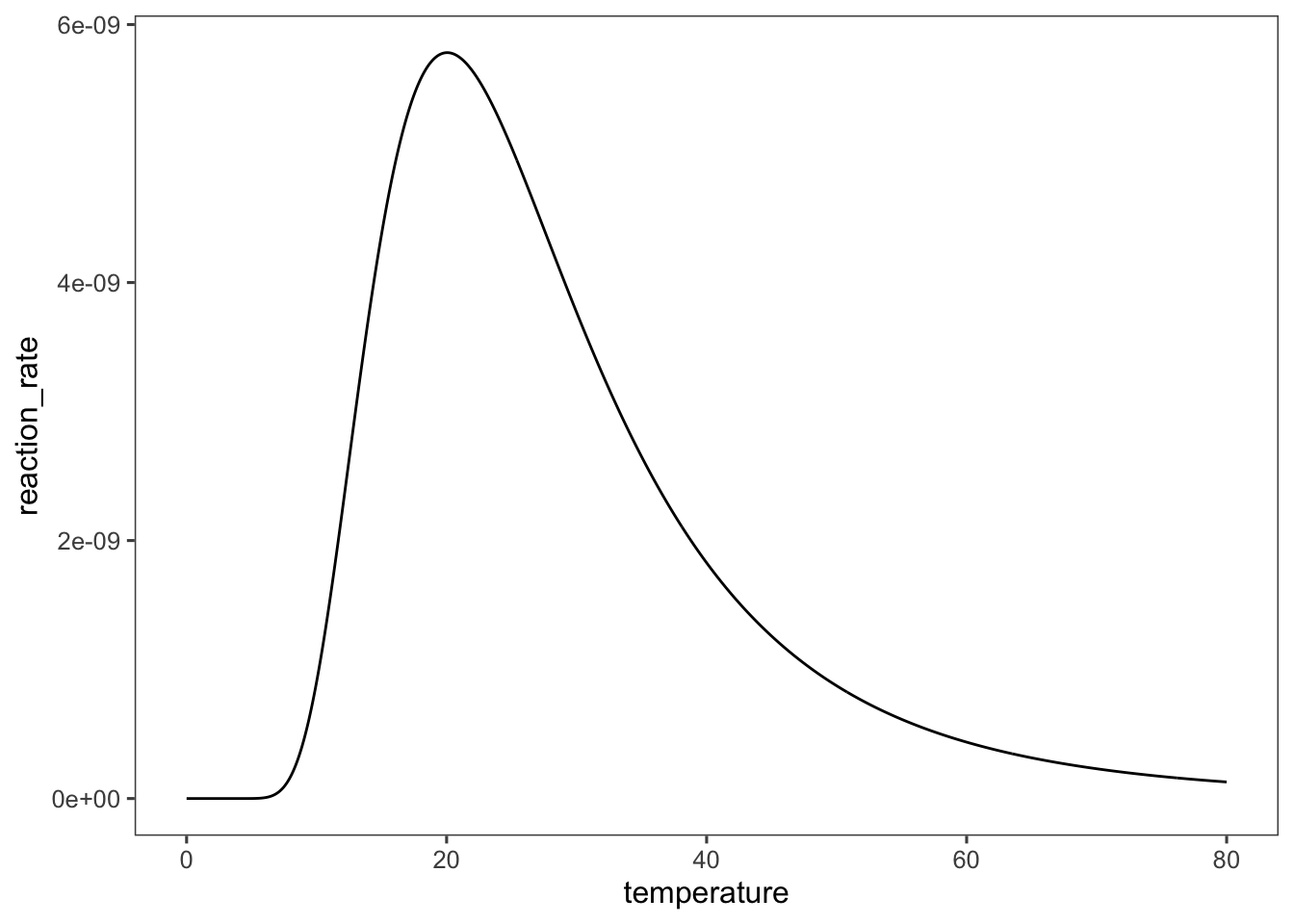

Unfortunately, enzymes—the biological catalysts—are polymers held in their catalytic conformation by non-covalent interactions, which are also sensitive to increases in kinetic energy. At high temperatures enzymes will unfold in a process called thermal denaturation. This leads to a temperature optimum for enzymatic reactions which is typified by the graph below. As temperature increases so does the enzyme activity and rate of reaction, but eventually the enzyme begins to unfold and the activity drops.

temperature <- seq(0, 80, 0.1)

A <- 10000

E <- 1000 #(kJ/mole)

R <- 8.314 #(J/mole/K)

K_eq <- 2e-04

reaction_rate <- A * exp(-E/R/temperature)/(1 + K_eq *

(R * temperature)^6)

data <- tibble(temperature, reaction_rate)

require(ggplot2)

ggplot(data = data, mapping = aes(x = temperature,

y = reaction_rate)) + geom_line()

We will describe this behavior mathematically later on, when we derive the rate equation for enzymes.

2.3.3.3 \(f(C_i)\) decreases as the concentrations of the reactants decrease

For a given temperature the rate of a reaction will decrease as the concentrations of the reactants decrease. This generalization again is true for most elementary reactions, but is violated in many enzymatic (and other catalytic) reactions, where extremely high substrate concentrations can inhibit some enzymes. We will also discuss this behavior while deriving the rate equations for enzymes.

2.3.3.4 \(f(C_i)\) describes the order of the reaction for each species

This generalization dictates that \(f(C_i)\) can be written as the product of all species raised to their “order” in the reaction. \[f(C_i) \approx \prod_{i} C_i^{\alpha_i} \] where \(\alpha_i\) is the order of the reaction for species \(i\). The order of reaction generally ranges from -2 to 2 (fractional values are permissible). The summation \(\sum_i \alpha_i\) is referred to as the overall order of reaction.

The order of the reaction for a species reflects the sensitivity of the rate of reaction to a change in concentration of species \(i\). If \(\alpha_i = 0\) then the reaction rate is unaffected by the concentration of \(i\). If \(\alpha_i < 0\) then the reaction rate is slowed—or inhibited—by \(i\).

Rate equations which obey this behavior are called power-law rate equations. These equations are grounded in thermodynamics governing molecular collisions between reactants and are often a useful starting point for analysis of kinetic data. Using a power law rate equation to describe the reaction: \[\ce{(-\nu_{A})A + (-\nu_{B})B -> \nu_{C}C + \nu_{D}D}\] we would propose that \[f(C_i) = C_A^{\alpha_A}C_B^{\alpha_B}C_C^{\alpha_C}C_D^{\alpha_D}\] The reaction orders cannot be determined from the stoichiometry of a reaction, i.e. \(\alpha_i \ne -\nu_i\). There are many ways to write a balanced stoichiometric equation for a reaction, the coefficients can be multiplied by any number. The reaction order reflects the actual behavior and mechanism of the reaction. We cannot assume to know which balanced equation reflects the mechanism, but we can hypothesize a mechanism and check if kinetic data fits. We will do this in a later section.

In the case that the reaction orders match the stoichiometry of the reaction as written, this reaction is called elementary. Elementary reactions are critical the development of reaction mechanisms and kinetics. We will discuss elementary reactions more in the next section.

Once again, for enzymatic reactions, this generalization does not hold. We will soon see enzymatic reactions are more representative of multiple reactions. This generalization may hold for the individual reactions comprising the enzymatic mechanism. But for the reaction as a whole, we will soon see, the order of reaction varies with substrate concentration.

2.3.3.5 For reversible reactions, the net rate is the difference between the forward and reverse reactions

\[-r_{A,net} = -r_{A,f}-r_{A,r}\] Here \(-r_{A,net}\) is the total rate at which the reaction proceeds and species A is a reactant as the chemical equation is written. The reaction is moving forward, if \(-r_{A,net}\) is positive, because the rate of consumption of A in the forward reaction, \(-r_{A,f}\), is greater than the rate of formation of A by the reverse reaction, \(r_{A,r}\). Don’t forget the convention that rates of reaction are positive and the sign is determined by the stoichiometry of the reaction.

Based on this generalization we can derive the equilibrium expression for a reversible reaction. At equilibrium the net rate of reaction is 0 and we can write out the rates of the forward and reverse reactions according to the order of reaction in each species. \[0 = -r_{A,f} - r_{A,r} = k_f \prod_i C_i^{\alpha_{f,i}} - k_r \prod_i C_i^{\alpha_{r,i}}\]

Rearranging we define the the equilibrium constant, \[ K_{eq}^C = \frac{k_f}{k_r} = \prod_i C_i^{(\alpha_{r,i} - \alpha{f,i})}\]

This was derived completely from the principles of kinetics. An equilibrium constant can also be derived via thermodynamics. As you might remember from thermodynamics: \[K_{eq} = \prod_i a_i^{\nu_i}\] where \(a_i\) is the activity (or “effective concentration”) of species \(i\). This expression for the equilibrium constant depends on the way the stoichiometric coefficients and thus the way the chemical equation is written. For a typical aqueous reaction we can write this equation in terms of concentration \[K_{eq}^C=\prod_iC_i^{\nu_i}\] Comparing the thermodynamic and kinetic definitions of \(K_{eq}^C\) we can see potential for inconsistency depending on how our chemical equation is written. This implies that in order to be thermodynamically consistent we must define the equilibrium constant based on a single balanced chemical equation. By setting the two versions of the equilibrium constant equal, we can define the condition for this correct equation. \[\nu_i = \alpha_{r,i} - \alpha_{f,i}\] Simply, the stoichiometric coefficients must be equal to the order of the total reaction.

2.4 Elementary reactions

The above statement defines an elementary reaction, i.e. the order of the forward reaction with respect to species i is equal to the number of molecules of species i participating in each individual reaction. The same is true for the reverse reaction. So for the simple example reaction \[ \ce{2A <=> B} \] the rate of the forward reaction is given by \(-r_{A,f} = k_f C_A^2\), and the rate of the reverse reaction \(r_{A,r} = k_r C_B\). Combining the two rate equations we find the net rate of disappearance of A is \(-r_{A,net}=k_f C_A^2 - k_r C_B\). In these equation the rate constants are defined in terms of A so the units of \(k_f\) are (volume/mole A-time) and the units of \(k_r\) are (mole A/mole B-time). Unfortunately, the units first order rate constants are often written just as (time-1).

2.4.0.1 ???Questions???

How would you write the net rate of formation of B?

Using stoichiometry, \(r_B = \frac{1}{2}(-r_A)\). Similarly the rate constants can be rewritten in terms of B.

2.4.1 Properties of Elementary Reactions

What assumptions can we make to help us propose elementary reactions?

An elementary reaction—a single-step, molecular level event—must be simple. It likely only involves two molecules, as termolecular collisions are very unlikely, and such collisions happening in the correct orientation are even less likely. We can also assume very few bonds will be formed or broken in a single step.

Elementary reactions cannot involve fractional molecules.

Elementary reactions must obey the principle of microscopic reversibility. Microscopic reversibility means that the reaction must follow the same mechanism in the forward and reverse directions. This means that an elementary reaction must be elementary in both directions.

With this framework for writing elementary reactions we will in Chapter 4 begin deriving mechanisms and rate equations for more complex reactions, which are actually series of multiple elementary reactions.

For now we will assume all of the reactions we are dealing with are elementary, unless we are given a rate equation, and we will begin to examine the kinetics of reactions in ideal reactors.